At the root of early 20th century Russian theatre is the carnival. Its raucous, undisciplined irreverent voice can be heard down through the ages from Pushkin, to Gogol and Dostoevsky, but its principle appearance in early Russian 20th century theatre was in ‘The Fairground Booth’ or Balaganchik written by Alexander Blok and directed by Meyerhold in 1906. An alternative title is also ‘The Puppet Show’. Balaganchik is taken from the word Balagan which is derived from a Persian word meaning balcony.

But what was the Russian Fairground, how did it become the mainstay of what amounted to a revolution in the Russian Theatre.

Konstantin Makovsky – Open-Air Festival During Shrovetide on Admiralty Square in St. Petersburg

In the 18th and 19th centuries, fairground performances were a common form of popular entertainment which also had their roots in the medieval Russian entertainers Skomorokhi who travelled around the country performing folk dramas and satirical pieces. Their performances were a commentary on the lower classes of Russia (See Tarkovsky – ‘Andrei Rublev’ and the punishment of Skomorokhi).Their message had a political charge. They were banned in 1648 by the then Tsar who feared that they were making Russian peasants more socially and politically aware. The fairgrounds showcased entertainers such as acrobats, clowns, puppet showman, tumblers and performing animals. One of the favourite characters was Petrushka; ugly and provocative, and acting the fool and cruelly ridiculing all around him. He personifies the ambiguous atmosphere and underlying menace of the fairground. He was always on the verge of breaking taboos, ridiculing figures of authority and meting out murder, mayhem and violence to those around him especially his wife. This ambivalence between form and content has always been a characteristic of Russian popular culture where laughter and tragic, serious and funny inhabit the same hemisphere so to speak.

The characters of this Commedia dell’Arte also became popular at the fairgrounds and it is believed that either Petrushka was the forerunner of Pierrotor maybe the other way around. However, it has to be said that Petrushka is of a different nature than Pierrot in many ways, although there is probably a lot of cross-pollination.

After the Napoleonic wars, Russian aristocrats divested themselves of French entertainment. At the same time, the fairground was frequented by aristocrats to demonstrate a national consensus and ‘narodnost’. Nicholas 1st made many visits to the fairgrounds.

Konstantine Somov – Harlequin and Columbina

However, this began to change and the rich began to move away from such entertainments. In this context, the Russian craze for serf theatres also declined. Abandoned by their owners, the serf actors gravitated to the fairgrounds in cities and towns. By the 1850s the European Harlequinades were complete with shows or pantomimes of a Russian hue, celebrations of famous battles or historical events. This brought a new public and the harlequinades began to cater for the demands of this new public. The audience became more plebeian after the emancipation of the serfs in 1861, and industrialisation brought more and more people in larger numbers to the cities of Moscow and St. Petersburg. At this time, entertainment changed with new industrial technology and mechanical attractions, roller coasters and large-scale pantomimes with large mass casts.

Detail from painting Boris Kustodiev Fairground Booths

We can imagine the scene of large crowds thronging and jostling with each other to see the latest spectacle or freak show and ride on a new-fangled attraction. In the background, the loud hum of the bustling crowd and the shouts and cries of hawkers and spectators, the aristocratic and the squalid rubbing shoulders in the same space. The many balagans or booths and entertainments created a kaleidoscopic cacophony of confused sound, blending into an almost Stockhausen type of symphony which could make a child’s head spin with delight and fear. Devil’s and clowns together would shout down from the balagan, competing with each other to entice the crowds into their theatre.

A description from the time gives a flavour of the atmosphere on the Field of Mars in St. Petersburg.

The Field of Mars roars and hums, hums and groans, bathed in a sea of lights all the colours of the rainbow and flowers……And the sounds? This is not sounds, it is a chaos of sounds. It is a gigantic, miraculous formless chaos. A barrel organ squeaks, a trumpet roars, bells clang, a flute sings, a drum hums, conversations, exclamations, shouts, laughter, cursing, song. There is a holiday carousel decorated with flags, lit up, decked out, illuminated. And here is a barker with his linen beard, the classic barker, that eternal jester, but a jester who holds the whole crowd in his hands, a jester who has power over them and, with a single word, forces the crowd to laugh, to laugh until they cry.

Here we have the cacophony of a new urban industrial environment with all its new social elements colliding in this brash, chaotic gathering.

Interestingly, commentators have noted that this description could be taken straight out of Gogol’s description of Nevsky Prospect in his story of the same name.

Alexander Benois Set design for opening of the ballet Petrushka 1911

The balagan theatre on the surface seemed crude and primitive with noisy interjections from the crowd who were completely involved in the performance. The balagans were pure theatre with little reference to any literary refinement. Both funny and frightening, they were grotesque and were not true to life as conventionally understood. The dramatic conventions of the fairground were staged in line with a popular view of the world, which seemed strange to the educated liberal intelligentsia. The balaganfairground was a space where different types of people could exist side by side, in some sense it united people often with contradictory characteristics and backgrounds. Those who worked the fairground were not easily classified and seemed outside the normal run of social strata in a kind of class unto themselves, (much like the kabukiin Japan).

Reproduction of the set design for Blok’s “Balaganchik” by Nikolai Sapunov 1906

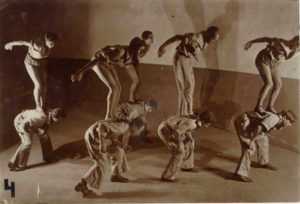

The life of these entertainers was hard and uncertain and in many cases it was a matter of simple survival. They were drawn from the bottom end of profession. The simplest acts were those which could be performed impromptu by acrobats, dancing bears, clowns, street musicians. The smaller shows were the most daring, and bore the spirit of carnival. It is to this pressed and squeezed aggressive type of show that Peterushkacame from. The ballet Petrushkathe Puppet morphed from the Italian Punchinellabut the Russian version can be traced possibly back as far as the 16th century with glove puppets and marionettes at Yarmarki(street fairs or markets). Vulgar with its mangled caricatured deformed figure, grotesque and sinister, violent with a squeaky voice unnatural voice.

The Petrushka show could transcend time and space. At various parts of the fairground and in various cities, Petrushka would be everywhere at once, and existed outside of time and space and yet could change and transform with the passage of time – he was both eternal and temporal simultaneously

The carnival atmosphere of the balagans provided material for artists and writers as diverse as Gogol, Dostoevsky, Benois, Dobuzhinsky and Somov. The carnival coincides with what is known as The Silver Age in Russian art with its all subversive overtones. The Silver Age liked farcical form because of the improvisational possibilities it provided. In his article on theatre, Blok argued for a theatre of action and passion which could be found in popular theatre. He saw in this a theatre of the future.

The theatricality of farce and the marionette quality of the balagan destroys the illusion of closed theatrical space underlined by Harlequin’s leap into a painted square of a window – into the void. In many ways the reality of the world of the fairground booth becomes more real than the that of the author, certainly fuller – by contrasting the theatrical illusion of farce with the reality of the author which in some way is no less an illusion. Here we are confronted with what constitutes reality and illusion where everyone’s perceptions of reality are confused but somehow valid, including that of the authors.

Bakhtin reminds us that carnival retains a wealth of assets invaluable to art with its ambivalence and capacity for transformation. In his book on Dostoevsky, Bakhtin outlines the main advantages of carnival as an aesthetic category.

Katcheli 1803 John Augustus Atkinson

Bakhtin states that carnival is not essentially a literary or artistic phenomenon as such but is a syncretic pageantry, which can be defined roughly as the attempted reconciliation or union of different and opposing principles, practices, or parties, as in philosophy or religion in the context of an elaborate public spectacle illustrative of the history of a place, institution, or similar. It is often given in dramatic form or as a costumed procession, masque, allegorical tableau, forming part of public or social festivities of a ritualistic nature. It is complex and varied in form with different expressions dependent on the epoch or time in history. It has an entire language of symbolism, and this entails sensuous forms from large complex mass actions to individual gestures, and as a language has given expression to a unified carnival sense of the world throughout all its forms and appearances.

Alexander Blok

Importantly from the point of view of the play by Alexander Blok: ‘The Fairground Booth’, Bakhtin notes that this language cannot be translated in any full or adequate way into a verbal language. In other words, it’s not a text and cannot be rendered as a text in words and phrases or sentences. However, it can be transposed or rendered into a language of artistic images that has something in common with its concrete and sensuous nature both in literature and the theatre especially. Bakhtin does not describe it wholly in these terms as he is essentially concerned with literature. It is Meyerhold and Blok who harness the language of carnival for theatre, where carnival is a pageant without footlights and without division into performers and spectators. In carnival, everyone is an active participant, everyone communes in the carnival act. It is neither contemplated or in a strict sense performed. The participants of carnival live in it and live by its laws; they live a carnivalistic life with its own mores and reality. In this sense carnival life, because it is drawn away from the normal everyday life, is life turned inside out, the reverse side of the world.

Vsevolod Meyerhold

For Meyerhold, carnival portended a theatre which was not dominated by the word and text but by movement and gesture and a breakdown of the naturalistic view of performance. It enabled the possibility of breaking out of theatrical conventions of the time, and the creation of new dramatic forms based on the very essence of theatre. The most popular and well-known version of such a spectacle in Russian culture is the ballet ‘Petrushka’. Here the elements of dance, theatre, balagan, Russian music and folklore and many of the concerns of modernism like the role of puppets and humans in art, come together in Stravinsky, Benois and Fokine’s ballet which was championed by Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe.

Announcement of my new book “Blok Meyerhold and The Fairground Booth” which was published a few weeks ago. The book is now available on Amazon. Blok wrote the play The Fairground Booth in 1906 in the wake of the 1905 revolution which was seen as a precuser to the 1917 october revolution. As Blok himself said it seemed he “dragged it up out of the police department of his soul”. The play itself was received with a mixture of derision and delight when it was first perfromed by Blok and Meyerhold in 1906.

Announcement of my new book “Blok Meyerhold and The Fairground Booth” which was published a few weeks ago. The book is now available on Amazon. Blok wrote the play The Fairground Booth in 1906 in the wake of the 1905 revolution which was seen as a precuser to the 1917 october revolution. As Blok himself said it seemed he “dragged it up out of the police department of his soul”. The play itself was received with a mixture of derision and delight when it was first perfromed by Blok and Meyerhold in 1906.

Excellent news about the film

Excellent news about the film